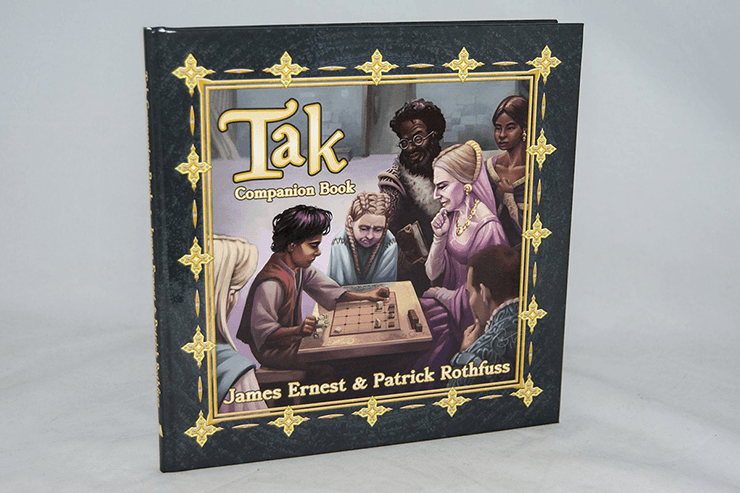

Games drawn from fiction obsess me: Quidditch, Sabacc, anything made up by Yoon Ha Lee, et cetera. So when it came to my attention that Patrick Rothfuss had partnered with a game designer to make a real-world version of Tak, one of the games Kvothe plays in The Wise Man’s Fear, I had to check it out. (The story of how it came about is pretty funny, and very Rothfuss.)

There’s a lot to say about the game—the worldbuilding fiction that has been built around it in the Tak Companion Book, the on- and off-line communities that have developed—but today, let’s explore how well the board game by James Ernest fits with the descriptions in the book.

As a writer, when you come up with an element like a game or a similar novel form of sport or entertainment, especially in fantasy, you need to make it sound like it has a full set of rules, strategies, variants, etc. So does Ernest’s Tak correspond to the drips and drabs of description that we get about the game in the book? And how well does it fit with the world Rothfuss created?

Note: for the purposes of this article, I am using only The Wise Man’s Fear, and not the detailed and utterly delicious Tak Companion Book. Tak has taken a life of its own in that slim volume, and here we are exploring how well the board game aligns with what we know of it only from the original descriptions in the novel.

Kvothe is introduced to Tak when he is bored out of his skull in Vintas and a grandfatherly noble appears in his rooms uninvited:

“You may call me Bredon,” he said looking me in the eye. “Do you know how to play Tak?”

Ah, the grand tradition of old folks introducing their favorite games to a new generation of bored, clever kids. Always followed by another tradition: the bored, clever kids expecting to master the game in a few rounds, just like they have mastered all of the challenges they have faced so far. The alphabet? Easy. Multiplication tables? No problem. How hard can this be? Which leads us to the third and grandest tradition of all: the little puke getting soundly destroyed by the elder.

(I have to confess to a bit of schadenfreude at watching Kvothe come across something he wasn’t immediately good at. I’m not proud of it.)

The Physical Game

All we can say for certain about the physical makeup of Tak is that it is played with “round stones” of “different colors” on a “small table.” The stones must be “sorted out” before play. We can assume the board itself is laid out in a square, since Bredon compliments Kvothe on “getting clever in the corner here.” We can assume that it might look similar to Go.

In Ernest’s board game, the layout is indeed square. The pieces, though, are more complicated than simple round stones. They are trapezoidal or roughly half-moon-shaped, built to be either placed flat or stood on one side as “standing stones”. In addition, there are “capstones,” which are built more like chess pieces and have their own rules.

So, a bit of a leap to get from some nondescript (or at least barely-described) stones of the books to Ernest’s game pieces, though the basics remain the same. There is also no reason that the pieces couldn’t be of a different style than Bredon’s set, I suppose. But this seems to be an area where some license was taken.

Mechanics

There are defenses and attacks, traps and tricks. Stones are placed on the board one at a time, apparently in alternating turns. Kvothe describes being beaten in many ways—but never winning, much to my delight. It is generally a long game when played by two well-matched opponents, though we can assume that Bredon beating Kvothe in “about the length of time it takes to gut and bone a chicken” as being a short period. (I am no scholar on chicken butchering—please provide an estimate in the comments if you have one.) In a lovely passage in Chapter 65: A Beautiful Game, Bredon describes the subtlety and possibilities for complicated and beautiful strategies despite the simple rules.

Here’s the tough part. Never mind if the stones are round or not—does the experience of playing Tak feel like the game described by Bredon and Kvothe?

Compared to contemporary games, which are often chided for taking longer to explain than to play, the rules of Ernest’s Tak are truly simple. In short, you’re looking to get your pieces in a line from one edge of the board to another. With the exception of the capstones, no piece does anything different than any other.

The game is open enough that what appears to a tyro like me to be deeply strategic play is not only possible, but almost necessary. People publish Tak problems online, after the nature of chess problems in which a difficult play is meant to be solved. A notation was invented, allowing players and enthusiasts to review every move in detail. It’s pretty heavy. It’s very easy to imagine a bard/wizard/actor/engineer getting lost in this game the same way people get totally preoccupied with chess, and to imagine an old noble desperately searching for someone to teach how to play at his level.

The World

The people of the Kingkiller Chronicle do love their entertainments. The taverns all have live music. Making a living as a travelling theater troupe is perfectly viable. Students from the University can be found playing Corners at the Aeolian all the time. Even the murderous, alluring Felurian gets in a round of Tak in her free time. (I expected that scene to open up a world of the seductive possibilities of board games. Physical proximity, very particular etiquette, opportunity for double entrendres—there’s a lot to mine there. But then Felurian doesn’t have much need for seductive arts…and Kvothe probably wouldn’t realize what she was doing, anyway.)

In practice, Ernest’s Tak fits in seamlessly with this conception of Temerant and its culture. It’s simple enough in construction to be a pub game. Little imagination is required to picture a grid painted on a table in every establishment Kvothe wanders through—the simplicity encourages wondering how different a board in an Adem barracks would look from one used by a tired farmer in the Waystone Inn. In bringing Rothfuss’ fictional game to life, Ernest has crafted an intriguing diversion which rewards careful thought and study—and is ultimately very believable as the lifelong hobby of someone with the kind of time a Vintish noble has on his hands.

Alex Livingston lives in an old house with his brilliant wife and a pile of aged video game systems. He writes speculative and interactive fiction, most recently the cyberpunk novella Glitch Rain. He’s on Twitter as @galaxyalex.

Alex Livingston lives in an old house with his brilliant wife and a pile of aged video game systems. He writes speculative and interactive fiction, most recently the cyberpunk novella Glitch Rain. He’s on Twitter as @galaxyalex.